The Story of Boudica

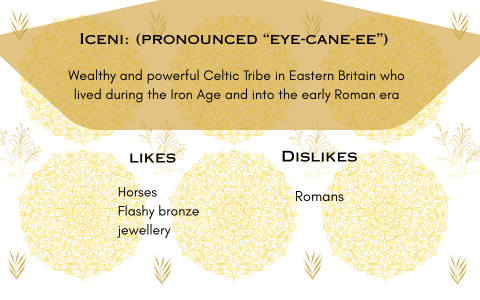

What we know of Boudica spans approximately two years of her life in 60 or 61 CE (Common Era). She was married to Prasutagus, leader of the Iceni people, they had two daughters and he’d recently died. He’d left half of his lands to his daughters and the rest under tribute to the very reasonable and calm, Emperor Nero. The Romans conquered the island approximately a generation previous and like most places conquered by the Romans, who were not at all bureaucratically and maniacally violent. The people were unhappy. Aggressive behaviour and heavy taxation by the Empire were taking their toll.

Garrisoned nearby were a group of retired and near-retired Roman soldiers. They were the types of men who spent twenty five years fighting for the Empire and were gifted citizenship at the end of it.

The abuse and heavy taxation against the Iceni continued and eventually erupted with the public flogging and sexual assault of her daughters.

Boudica, the Mother

A mother will take an untold amount of pain until it is turned on her children. Boudica is the story of independence and revolution against imperial might but it is also a story of fierce motherhood. It was never the public flogging or the heavy Roman taxation that fuelled her feral rage and led her army into the throes of battle. It was her daughters.

I imagine the moment Paulinas’ slaves or soldiers (depending on the telling), entered Boudica’s roundhouse where her daughters cowered, was the moment her mind snapped and all the anger and hurt welled in her chest and exploded out of her limbs. It was this anger that drew her sword and propelled her charge forward. She slayed soldiers, splitting their necks and crushing their skulls where they stood. Each death, intimate and up close as they fought with swords and clubs, avenged some small part of the violence visited upon her daughters’ bodies.

The story goes, she and her rambling army of Iceni men, their women and children alongside to watch the spectacle, laid waste along to the way Londonium. Along the way, they burnt down Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester). They took no slaves. The Roman historians took note of this, and I think it points to a binary view of life (freedom) or death, there is no place for slavery. Enslavement suspends the experience of living.

Boudica was obviously able to lead, but a citizen army can only do so much against a well-trained professional one. The Iceni were drawn into an impossible to maneuver chasm and slaughtered.

On campaign, once settled for the night, when fires crackled down to burning embers, the sounds of snoring and murmurs to the gods her only company, she could loosen the hard ties binding her heart and weep with sorrow. The other side of grief-filled rage is a well of sadness that blankets your mind and suffocates all thought.

The story of Boudica and her rebellion is uncomfortable and fascinating because essential to it its overall myth is a mother’s pain. The Elizabethans and Victorians were happy about all the small and mighty underdog sabre rattling they could do with Boudica as their totem.

Mothers who respond with their own brand of violence and resistance, they are feared and made monstrous. We really only know of Boudica through her violence against the Romans who cast her as excessive and wild and while I think the emotions and rage are true, it doesn’t necessarily mean that’s all she was to the Iceni people. Or that the Iceni people can be represented in one revolt.

The other side of Boudica’s story (and likely true, since it came from Tacitus) is that her revolt was sparked by heavy Roman taxation and general ill treatment because “the Romans were bastards”, to quote Emma Southon. Her husband dead, the tribe turned to her, a woman. Unfathomable and confusing to the Romans. You want a woman to lead?! Boudica is then fearsome leader, assembling the Iceni masses and standing up against injustice. She rallied them with inspiring speeches and her own bravery.

She is available to represent woman’s anger, pain and vengeance. The archaeological record still holds her furious burn line under 2000 years of dirt. Women and mothers are so often supposed to be soft and demure, a calming influence. Women’s pain is uncomfortable to witness because sometimes it taps into a well of thousands of years old hurt.

It doesn’t really matter if Boudica was reacting to the brutality wrought upon her people or an assault on her daughters, it’s that she did it. She led when people were hurting and needed it.

Listening to Boudica

The Ancients podcast, hosted by Tristan Hughes has had a few deep dives into Boudica’s life, the revolt and then life for the Iceni after the revolt. Hughes is an excellent and interested interviewer, he leaves space for the historian to speak freely and really explore the fascinating history of this woman and the time period.

Other sources that have informed my impression of Boudica include Emma Southon’s appearance on Betwixt the Sheets. Inexplicably, the only copy of “A History of Rome in 21 Women” at my local library is in Polish? She is a great authority on Rome and heaps of fun to read and listen to (I’ve read A Rome of One’s Own – recommend!).

The boys at The Rest is History cover Boudica exactly how you think they would but there are no accents from Tom. On History Hit, Dan Snow is loud and posh about Boudica. It’s not a fatal criticism of the lads, they tend to cover women on their podcasts in a brash or weirdly fawning way (yes, this is about Emma Hamilton and Tom). They’re much better for military history that feature men.